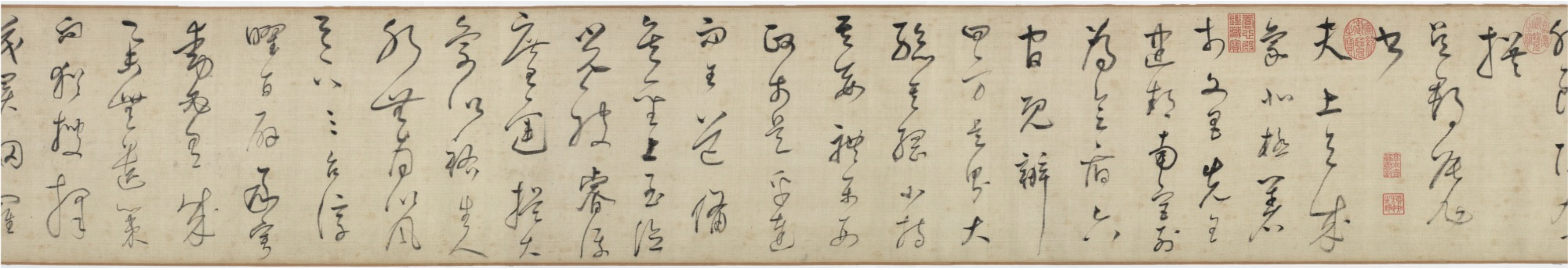

The papyrus scroll, (excerpt from The Book)

by Amaranth Borsuk MIT Press

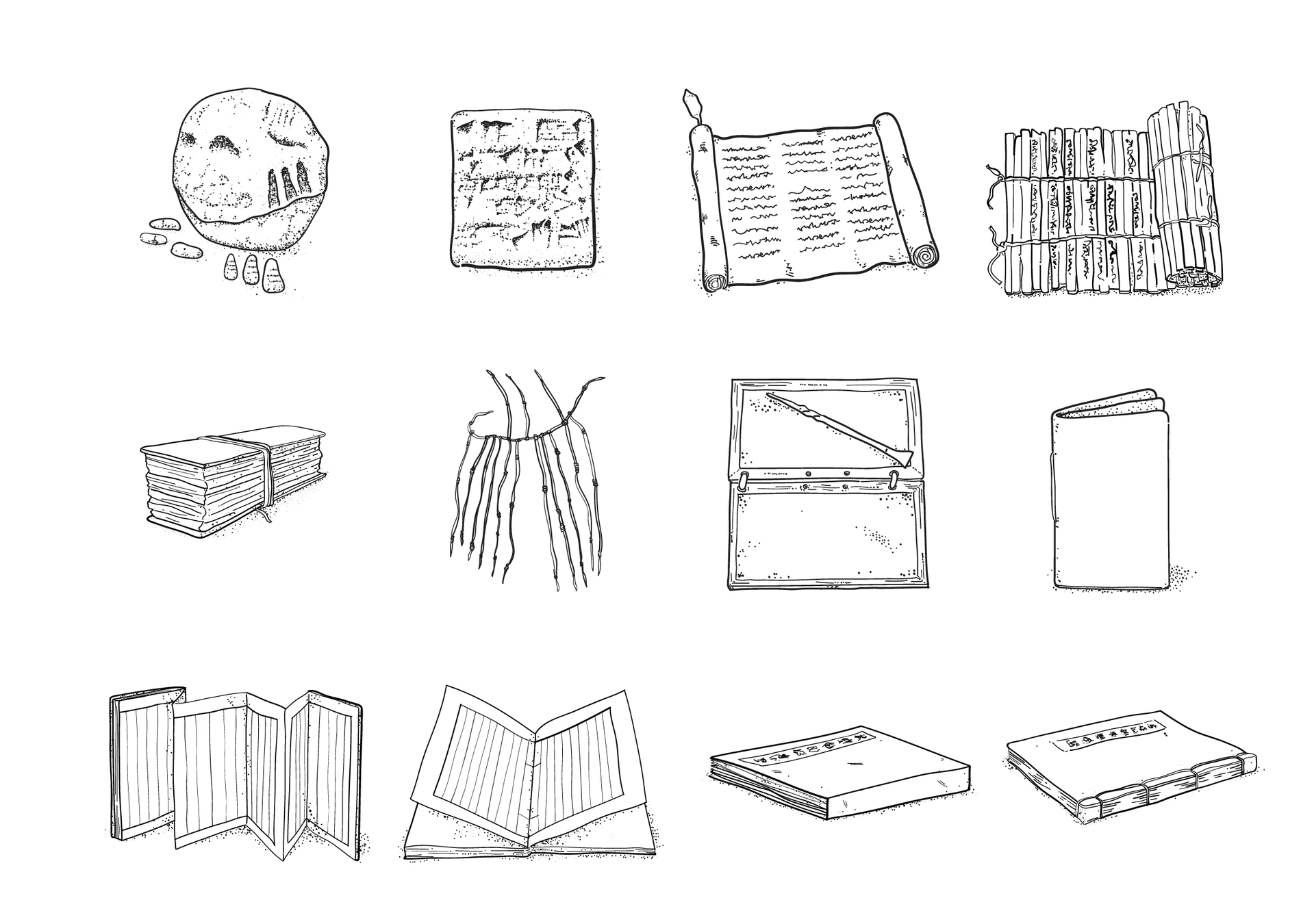

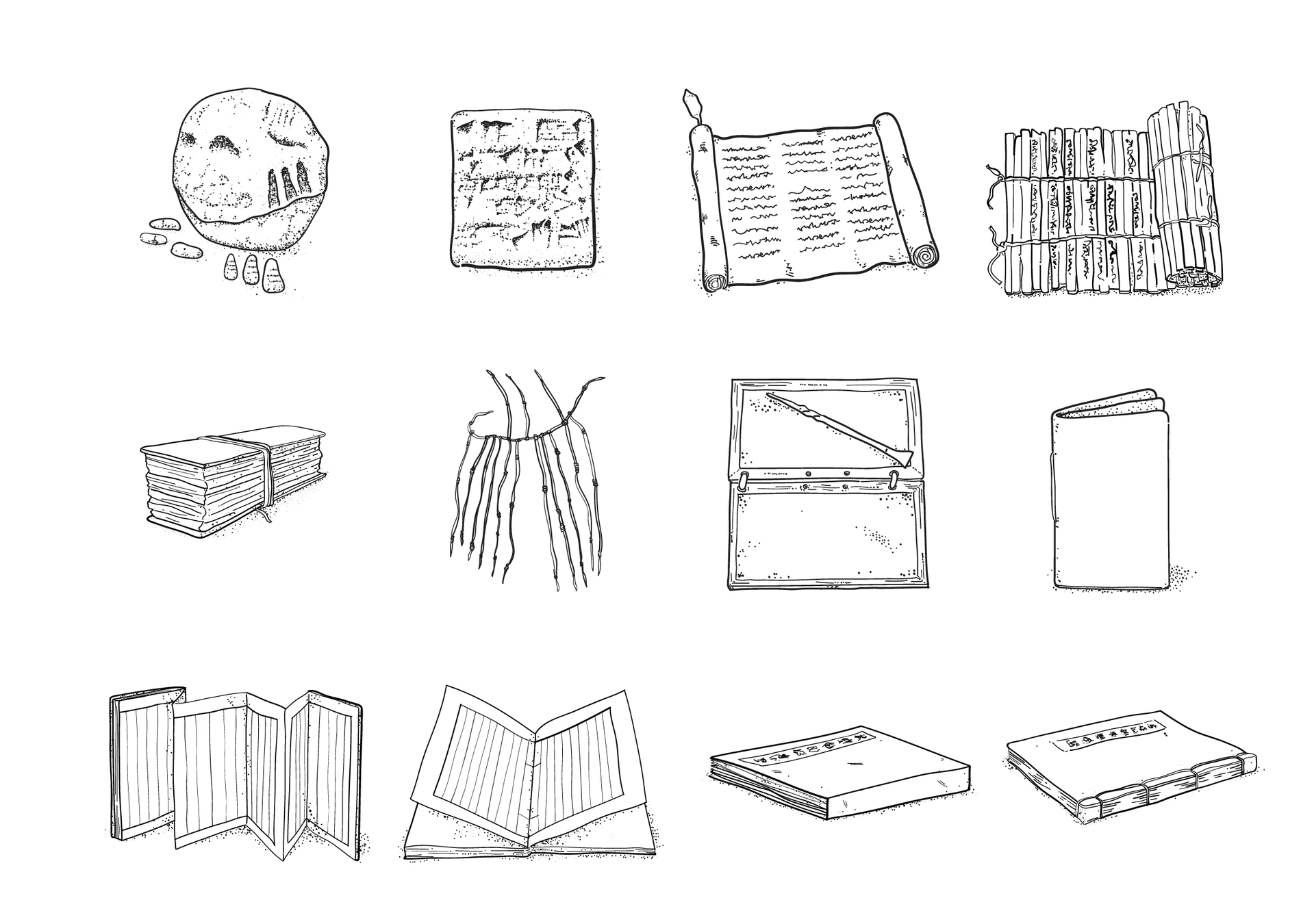

While the Sumerians were developing a book from the materials at hand, the Egyptians reached to their own river for a support to writing: papyrus, which only grows in the Nile Valley. Egyptians used the plant widely: for building materials, clothing, and even food. The earliest Egyptian writing appears on stone faces inscribed with hieroglyphics that date from the fourth millennium BCE. Hieroglyphics are sure to be familiar to many readers as a system in which drawings of figures and objects are combined to represent things (pictogram), ideas (ideogram), and sounds (phonogram). Hieroglyphs were inscribed on temple walls and obelisks, providing religious and historical records, but they also appear on potsherds as more ephemeral notes. As the need for documentation increased and Egyptians sought a more portable surface for writing, they developed an ideal material from papyrus: a paper both smooth and flexible that could be sized to the needs of a given document.

To write on this surface, they developed a water-soluble, charcoal-based black ink and a red ink from oxidized iron, as well as a brush-like rush pen that allowed for smooth and rapid transcription, which gradually transformed hieroglyphics into a simplified script known as hieratic. One of the many ways the material form influenced its content was the indistinguishability of up-and-down strokes in hieratic, which some scholars associate with concern for piercing the papyrus. The uniform thickness of the line suggests even pressure, unlike the thick downstrokes and hairline upstrokes associated with calligraphy on paper and parchment. It might also be attributed to the reed pen itself, a soft brush with a fine tip. Whatever the case, in the fifteen hundred years in which papyrus prevailed, scribes took great advantage of their chosen medium.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE) provides a useful, if limited, explanation of Egyptian papermaking (a description he copped directly from Theophrastus) as part of his Natural History. The cyperus papyrus plant, which was used so extensively in ancient Egypt that it was nearly eradicated by the first millennium CE, consists of clusters of long, triangular stems (up to eighteen feet tall) with tasseled heads. Papyrus was made by cutting the stalks into uniform lengths, removing the outer green rind, and making strips from the plant’s pith using one of two methods. According to Pliny, papermakers sliced the pith into strips that gradually decreased in size (given the triangular shape of the stalk), discarding the smallest section. Contemporary research, however, suggests that in some cases the triangular stems were carefully peeled, working inward in a spiral fashion. This would have resulted in a wider continuous sheet and less waste. In both methods, these strips were laid out in two layers—one vertical, the other horizontal—and beaten until the fibers fused, using the plant’s natural sap as an adhesive. The resulting sheets averaged between eight to thirteen inches high and eight to ten inches wide, much like contemporary office paper. These were dried and bleached by the sun, then burnished with a piece of stone or shell, leaving behind a smooth white surface with natural flecks.

Egyptians glued these sheets end to end using starch paste to make rolls of twenty, which could be trimmed into shorter widths as needed and for easier handling. Such rolls were generally inscribed on only one side and in columns so they could be held open to reveal a narrow portion of text, much like a newspaper. The two layers of pith created a natural paper grain that dictated how papyrus could be inscribed and rolled: with the horizontal grain on the inside and the vertical on the outside to prevent cracking as the sheet curled. Once a scroll dried, its curvature would set, making curling it the other way difficult, so in those rare instances in which scrolls have been found with writing on both sides, the reverse generally contains a second text, suggesting reuse rather than continuation.

Among its affordances, papyrus was durable, could be extended by adhering additional sheets, and allowed texts written on it to be amended, unlike hardened clay. The smooth surface made possible the development of curvy hieratic script, and the use of the brush facilitated the development of colorful illustration, of which Egyptian papyri offer some beautiful examples. Among the best known is a collection of texts to facilitate passage into the afterlife, referred to by ancient Egyptians as the “book of coming forth by day.” Known colloquially as the Egyptian Book of the Dead, this collection of two hundred spells, originally written on burial chamber walls and sarcophagi, was codified around 1700 BCE, when it began to be composed on scrolls for interment with the deceased. The order and number of spells varied from roll to roll, and its design reflected the status of its owner: from elaborately illustrated custom versions for the wealthy, who both selected their preferred spells and were depicted within them, to more anonymous prefabricated templates with gaps for the name of the deceased.

The papyrus scroll contains precursors to both the codex book and contemporary digital reading devices. The scroll, after all, which allowed continuous writing in columns on a surface that could be thirty to forty feet long, provides the verb we use for horizontal or vertical movement in a text that extends beyond the screen’s bounds. Many finding aids developed for the scroll persisted into codex form. The work’s contents or first words and the name of its creator were written on the outside edge of the scroll, providing an early title page, though the unfortunate placement at the scroll’s vulnerable edge meant that most of these fragile bits were lost over time. Egyptian scribes took advantage of ink’s variety and incorporated rubrication into their work, using red ink to highlight important words and ideas, as well as to indicate the start of new paragraphs. Such contrast was not possible with cuneiform impression. Rubrication would be adapted by Greek and Roman scribes in their manuscripts, and the tactic persisted into early printed books. Headings, glosses, and titles might be written in red, as would dots and dashes used to separate sections and sentences. In every case, scribes developed techniques to facilitate the reading of written work, one of the hallmarks of the book as not only a storage, but also a retrieval device.

While papyrus facilitated the development of writing and illustration, it was not an ideal archival material because it becomes fragile as it dries and is susceptible to moisture and insects, particularly in European climates. We have very few intact papyrus scrolls as a result. Another drawback to the scroll form, its tendency to snap shut due to its curled shape, required readers to use both hands to hold it open or lay it on a flat surface and place objects on it, tactics that sounds cumbersome to us today, but that scholars point out would have become second nature among Egyptian readers. This normalization of reading practices bears remembering, since from the vantage point of the twenty-first century, our own codex book has been normalized to such a degree that we question the “book-ness” of anything that challenges our expected reading experience, with little regard for the fact that reading in one direction rather than another, scanning text silently, and putting a title and author’s name on a book’s cover are all learned behaviors.

Some scrolls were wound around rods that extended beyond the top and bottom of the roll to facilitate opening and closing. This umbilicus (a term that points to the rollers’ centrality but also suggests a Cronenbergian connection between the hand at one end of this cord and the text at the other) could act as a weight if allowed to drape over a table’s edge, holding the scroll open. Generally, readers would unroll a scroll with the right hand while rolling it with the left, an active process revealing only a column or two at a time, which meant that to read it again one had to rewind it, much like a reel-to-reel, cassette, or VHS tape. This process takes a ceremonial form in Judaism, where the Torah scroll is publicly rewound on a holiday known as Simchat Torah, or “rejoicing of the Torah.” After the final portion is read, the scroll is paraded around the congregation before being returned to the start so the opening portion can be read as well, symbolizing the cyclical nature of both the year and the text.

While one might expect parchment to have quickly superseded its more fragile counterpart, scrolls of both kinds existed side by side for centuries, much as tablets and scrolls did. Some scholars attribute this parity to the difficulty of systematizing and scaling its production. Parchment and vellum, its highest-quality exemplar (typically of calfskin), were made by skinning an animal, removing the hair from its pelt, bathing the skin in lime, stretching and drying it slowly, then treating the surface to make it hard and smooth. In addition to requiring utmost care, the process necessitated the slaughter of great quantities of livestock, a costly prospect. Much as in our own technological moment, where print books and e-readers continue to be used despite staunch proclamations in favor of the portability, durability, and cost-effectiveness of one or the other, established systems of production and use take time and resources to change.